Sunday, December 31, 2006

Warnie...Warnie...

I didn't get to see Shane Warne capture his 700th wicket in Test cricket (that happened on the first day), nor did I get to see him capture his 1000th international wicket (his Test and One Day International wickets combined), but I did get to see him in action, and in the context of an Australian victory in his last match at the 'G.

Warne is, as everyone knows, a controversial figure. Much of that controversy has been manufactured by the media's shameful invasion of Warne's private life, and by those odious individuals prepared to profit from our celebrity- and scandal-obsessed age. But much has also been generated by Warne himself. Like any flawed human being, he has done things that were thoughtless or stupid or downright crass. He has brought himself - and, it has been argued, the game of cricket - into disrepute on more than one occasion. No argument from me on that score.

But it is also undeniably true that Warne is certainly the greatest Australian cricketer ever, and arguably the greatest cricketer from any nation to have played the game. I do not posit that fact to excuse some of his less meritorious behaviour; I present it simply because it is the case. And it is a fact that exists independently of mere statistics and records.

Warne helped revitalise international cricket at a time when Test matches were considered dull and passe - indeed, when ODI's were thought to represent the totality of cricket's future. By utilising the hard-won art and skill of leg-spinning, Warne drew the attention of new generations of cricket lovers to the possibilities contained within the 5-day game. By approaching cricket with gusto and enthusiasm, he educated those inclined to dismiss Test cricket in its capacity for drama and tension. Most of all, Warne combined both flair and intelligence to effectively demonstrate that cricket could be both thoughtfully and entertainingly played.

True, Warne has sometimes let himself down on the cricket field as well as off, most notably when he got himself dismissed for 99 in the Test match at Perth against New Zealand some years ago. But those were occasional aberrations. As a cricketer, Warne was without peer, and Australia owes much of its success in the last 15 years to his once-in-a-generation talent.

And so it as fantastic to see Warne in action at the Melbourne Cricket Ground. Firstly, with a bat in his hand, which he wielded with wonderful aplomb to score a sprightly 40 not out. And then with the ball in his hand. He had to work a lot harder in the second English innings for his wickets than he had to do in their first dig; but eventually, he broke through, dazzling supporters, opponents, and team-mates alike with his skill. This was exemplified by the flipper he bowled to take the wicket of Sajid Mahmood. The flipper is a short-pitched ball which, because of the top-spin applied by the bowler as the ball leaves his hand, skids through at about ankle height to trap the batsman in front of the wicket, or which bowls him outright. It is a very difficult ball to deliver, and only the best can do it without any betraying change in their action, or without the ball simply sitting up to be dispatched by the batsman to the boundary. It is a ball with which Warne himself has had his problems; and yet, on this day, he produced the perfect specimen. A fitting tribute to both the cricketer and the occasion.

Warne has one more Test, in Sydney, to play before he bows out of the game altogether. But it was very special to see him in his last home Test; suitably, he was carried from the ground on the shoulders of his team-mates once the final English wicket fell, to the rapturous applause of the whole crowd of 80,000 people.

Talk to you soon,

BB

Quote for the Day: A genius is any person who can re-wrap a shirt and not have any pins left over. (Dino Levi)

The Art of Victory

My Dearly Beloved posed this question to me after we'd spent a day at the MCG watching the Australian cricket team wrap up the Fourth Test against England - courtesy of some tickets to the Members Stand provided by some wonderfully generous friends. The Australians won easily - indeed, the the English posted only modest scores in both their innings, and the Australians needed only to bat once; the subsequent victory to Australia by an innings and 99 runs was about as comfortable as any win at the first-class level gets.

What prompted my Dearly Beloved's question was not the understandable jubilation of the Australian players at their victory, or the generally celebratory nature of the crowd response to the game's outcome. Nor indeed was my Dearly Beloved disturbed by the mostly good-natured rivalry between the English and Australian fans, and the banter which this produced.

Instead, the question was prompted by the conduct of a single person: a woman sitting two rows behind us. Now, I'll admit that although I couldn't see this woman for most of the time, I was not well disposed toward her from the outset as she had a most unattractive voice: something akin to a bandsaw cutting through concrete. Hardly her fault, I'll grant you, but I did wonder as she gossipped to her friend through most of the day at the top of her voice why she had to be so loud. It was not as though the chanting which broke out at different times in various sections of the crowd made conversation impossible; and there were plenty of breaks in which there was neither cheering or chanting, and a quiet word with one's neighbour was perfectly possible. But the loudness and harshness of this woman's voice suggested some unattractive underlying personality trait; a suggestion that rose above simple bias by the content and manner of her conversation.

Although perhaps "conversation" is too generous a description. As I said, this woman's voice was quite loud, nor was its volume moderated in any way by her subject matter. And so she continued on with an almost embarrassing obliviousness to the sensitivities of others, dissecting the various scandals and other salacious affairs in which her friends, family, and acquaintances were at that time embroiled. I was neither interested in, nor did I want to know, who was having sex with whom, or who was in trouble with the Tax Office, or who was a bastard to work with. Not that I, or any one else within a considerable radius, had any say in the matter: this woman let us all know regardless. Moreover, she wasn't merely gossiping; she was engaging in what I call the "And then I said" mode of gossip. That is, every anecdote appeared to end with a cautionary sermon on how her sage advice in every matter had been ignored, with disastrous consequences. If only mere mortals had heeded her wisdom, all would have been well.

In other words, everything she said, and the way she said it, suggested she both had a smug, self-satisfied view of her own worth and wisdom, as well as taking an obvious delight in the misfortunes and foibles of others. Not the personality type to which I warm.

No, I was not well-disposed toward this woman. But what made my disposition less favourable was that, as the match (oh, yes, I was there to watch the cricket) drew closer to its inevitable conclusion - an easy Australian victory - this woman turned from gossip to bombarding those about her with disparaging comments about all things English. Every time an English player produced a good shot and scored runs, she would belittle their skill. Every time a wicket fell, or an English batsman had a near escape, she would laud the superiority of the Australians or suggest that it was only undeserved luck that had produced any English success in the past. Every time the English supporters tried to rally their side with chants or barracking, this woman observed with obvious relish that those same supporters would have 10,000 miles on their way back to England to contemplate their side's demise in this series.

Hence, my Dearly Beloved's question: "Why are Australians such bad winners?"

Now, don't get me wrong: I love Australia belting the Poms in the cricket as much as the next bloke. But what made this woman especially distasteful -aside from what her gossip revealed about her personality - was that her partisanship allowed for no acknowledgement of the merits of others. There was no sense of sportsmanship, of playing the game in a good spirit; that games, far from being one of many modes of developing the human spirit, were there only to be won. Moreover, not merely won, but won in such a way as to ensure the utter humiliation of the opposition.

Ultimately, however, what grated about this woman was the indication that she had no sense that cricket, afterall, is just a game. Granted, in the age of professional sports, it is a means of living for the players concerned; but this woman's response was one of excess, as though cricket, or any competitive sport in which Australia is involved, had a meaning and virtue in and of itself: namely, that Australia had to win, had to utterly thrash and humiliate the opposition, otherwise she would be lessened somehow, and life itself would be diminished. This woman had seemingly made an enormous emotional investment in Australia winning; such an investment, in fact, that there was simply no room for anything else.

Compare this attitude to an incident which occurred at the end of the Second Test when Australia last played England - in England, in 2005. The Australians had fallen agonisingly short of winning the game, a heartbreak rendered all the more wrenching because England had been well in control for most of the contest, and the Australian players had performed heroically well to get as close as they did. And yet, at the moment of triumph, one of the English players - Andrew Flintoff, who had been more responsible than most for the English victory - immediately went across to the disconsolate Australians to offer his congratulations for their efforts. There is a powerful photo of Flintoff on his haunches shaking the hand of the Australian player Brett Lee, one arm cast consolingly across Lee's shoulders, as Lee crouches, almost on his knees, sadly contemplating what might have been. It has been rightly lauded as the defining image of that particular series, because it speaks powerfully to the spirit in which the players conducted themselves: with determination to do their best and carry their team to victory, but in such a manner as left room for generosity and dignity and acknowledgement of the merit of others.

In that one instant, Flintoff conveyed a depth of spirit that the woman with the bandsaw voice seemed to lack entirely.

As for my Dearly Beloved's question, I am sure there are all sorts of sociological, psychological, and existential answers. The adoption of the "win at all costs" mentality; the importance which sport assumes in the lives of those who feel disempowered or disenfranchised; cultural cringe; anti-intellectualism; cultural arrogance; transferred compensation for personal feelings of inadequacy. And while all of these are undoubtedly true and accurate, it seems to me to be, ultimately, a question of spirit - and of the generosity of spirit. And it seems to me that the question of generosity of spirit offers us a clear choice: either we allow ourselves to enter into the lives of others, or we barricade our lives within the shell of our own being. If we do the former, we will expose ourselves to many misfortunes and setbacks; but we will be all the richer for the experience, and for the benefits which coming into contact with other lives brings. If we do the latter, we may very well be safe from the "slings and arrows of outrageous fortune", but our lives will be barren, empty, and always searching for some external source from which to find completion of our being.

Ultimately, beneath my dislike, I felt sorry for this woman; it seemed to me that she was entirely enclosed within herself, and could only find sustenance from the misfortunes of others, or from denigrating their efforts. Perhaps I am doing her an injustice, because I have only seen her within this one context. But it was a context that was powerful enough for me to conclude that, at the very least, her spirit of being was severely diminished or constricted. Afterall, if she conducted herself so spitefully in so trivial a context as a game of cricket, how did she conduct herself in important areas such as human relationships?

Talk to you soon,

BB

Quote for the Day: If a person cannot conduct themselves properly in trivial affairs, what hope is there that they will conduct themselves properly in important matters? (Confucius)

Monday, December 25, 2006

A Christmas Reflection

While I don't disagree with these interpretations, I have been reflecting on the meaning of Christmas with a view to going further in my exploration, to delving into the core of what is implied by the Christmas event.

It is widely known that the early Christian church was persecuted at different times and with differing degrees of severity during the Roman Empire (prior, that is, to the adoption of Christianity as the state religion of the Empire by the emperor Constantine). The common understanding is that this persecution was triggered by the Christians' refusal to participate in the state-sanctioned worship of emperors; by their convenience as scapegoats in times of political crisis or natural disaster; or as a consequence of misplaced rumours that Christians practiced cannibalism and/or gross sexual immorality. While this understanding is not without foundation, it does not articulate the deeper, more pervasive reason why early Christians attracted so much hostility.

This hostility had its origin in what is known as the "scandal of Christianity". This "scandal" arose from the Christian assertion that Jesus Christ was not just the Messiah anticipated by the Jewish faith, but was in fact God incarnate in human form; the Word, as is proclaimed in John's Gospel, made flesh. Now, the reason why this was so scandalous a notion arises from the prevailing view in the Mediterranean world at this time that the material world was inseparably divided from the spiritual world. According to this view, the world of "flesh" was corrupted, impure, and subject to decay and death; whereas the divine or supernatural realm - the world of the "spirit" - was pure, incorruptible, immortal and eternal. Thus, for Christians to suggest that, in the person of Jesus, God incarnated God's-self as a human being, was to suggest that the "pure" realm of the divine had become "tainted" by the "corruptible" world of the "flesh".

This was a notion that was deeply offensive to many people in the Roman period. And in the events commemorated by Easter - Christ's crucifixion, death, and resurrection - this offensive notion appeared to achieve its ultimate form. Were Christians seriously suggesting that God - the divine, the pure, the eternal, the ineffable and unknowable - actually suffered pain and death as a human being? And not just any old death - but a death that was degrading, humiliating, and utterly execrable: the death of a criminal, an outcast, a pariah? Nor did the assertion of Christ's resurrection cut any ice with those offended by the "scandal of Christianity": as far as they were concerned, you could not compensate for the outrageous notion of God reduced to the human by offering some countervailing assurance of ascendance or return to divinity. It just sounded like trying to be too clever by half.

This was the "scandal of Christianity", and it was the prevailing, underlying reason why Christians were variously feared or hated or distrusted. Indeed, it is why the early Christians were more than once accused of being atheists - because the notion of God made human, God suffering am utterly wretched and horrific death, sounded like a denial of God altogether.

And in considering Christmas, it occurs to me that, underneath the familiar, well-worn story about the Nativity, beneath the comfortable, familiar figures of the wise men and shepherds,the angels and Mary and Joseph, beneath even the figure of the Christ-child as well, the "scandal of Christianity" resonates as strongly as ever. Indeed, I think it resonates even more strongly than at Easter, demanding our attention.

Consider: even at a superficial level, most people are aware of the humble circumstances in which Jesus was born: in a stable, surrounded by farm animals and poor country folk. Granted, the presence of the wise men adds an element of gravitas; but the humbleness of the scene is underscored by the rural setting, by the fact that the momentous event of Christ's birth goes virtually unremarked by the world, and takes place in a rural backwater. Moreover, Jesus' parents belong to the unglamourous working-class; they're not royalty or nobility (despite being members of the house of David), or even wealthy traders or scholars, nor are they from the priestly class. In fact, they were hardly a step up the social ladder from the shepherds who attended Christ's birth.

But the really scandalous thing about Christ's birth was that his mother was not even married! Leaving aside the dispute about whether the original Greek text describes Mary as a "virgin" or a "young woman", the unassailable fact was that she was unmarried, and thus, given the patriarchal society into which she was born, in a highly vulnerable position. And if you want to understand how vulnerable, think about the prejudice directed toward unmarried mothers in our own society; consider the stigma that attaches to the term "unmarried mother". So not only did Christians - from the point of view of the "respectable" citizens of the Roman Empire -have the temerity to suggest that God had condescended to incarnate God's-self as a human being, they didn't even try and gild the lily by asserting his parents were powerful rulers or holy wise people or part of the well-regarded "establishment"! Quite the contrary: they went out of their way to proclaim that he was born to a poor unmarried couple in a rural backwater, attended only by shepherds and farm animals! The nerve! The cheek! The scandal of it all!

But why, you may ask, am I raising all of this? Because beneath the glitter and glib sentimentality, beneath the familiar story of Jesus' birth to which most of us have long since ceased paying any real attention, lies a simple, startling, scandalous fact: that God not only incarnated God's-self in the person of Jesus and thereby joined in our humanity, this incarnation was an act of solidarity with humanity. God was entering into our humanity and thereby declaring that the division between the human and the divine imagined by the ancients did not, in fact, exist. God incarnate in Christ was a proclamation that human fallenness and mortality were within God's power and subject to God's will; fallibility might be a condition of our being, and death might be the final end of our life on earth - but neither were absolute, and neither were the ultimate destiny of humanity. In entering into our humanity, God, through Christ, was articulating the promise, and the hope, of ultimate entry into communion with God.

The humbleness of Christ's birth was a declaration that salvation was not a matter of rank or reputation, nor was it conditional on human merit or effort; it was freely available to all humanity across all time, the free gift of God's grace to which are invited to respond. A response that can be made equally by all, regardless of the fallenness of their humanity or their station in the human society.

Talk to you soon,

BB

Quote of the Day: Christmas is that magical time of year when all your money disappears. (Hal Roach)

Saturday, December 16, 2006

Game Over

Woo hoo.

Talk to you soon,

BB.

Quote for the Day: I will. (BB)

Tuesday, December 12, 2006

The Vision Thing

It is at this point that one of the most memorable passages in Le Guin's novel occurs. Ged is given a boat by an old fisherman in order to continue his quest; and the passage that follows has remained with me ever since:

Unlike the shrewd fishermen of Gont, this old man, for fear and wonder of his wizardry, would have given the boat to Ged. But Ged paid him for it in sorcerer's kind, healing his eyes of the cataracts that were in the way of blinding him. The old man, rejoicing, said to him, "We called the boat Sanderling, but do you call her Lookfar, and paint eyes aside her prow, and my thanks will look out from that blind wood for you and keep you from rock and reef. For I had forgotten how much light there is in the world until you gave it back to me."

The reason this passage stuck with me was quite simple: as a child who suffered from severe myopia in both eyes, and who as a consequence was already wearing very thick spectacles (and which would only become thicker over time), I understood all too well the desire for unclouded vision. Laser surgery had yet to be invented (and would, in any event, prove to be inappropriate for my particular condition), nor had I reached an age where contact lenses could be utilised; so I had simply resigned myself to never being able to see except through the distorting lens of spectacles. Thus it was that I appreciated what the old man in the novel meant when he said he had forgotten how much light there was in the world; only, in my case, I had never really known.

As I grew older, I was eventually liberated from the burden of thick spectacles by contact lenses. First, soft lenses, and then hard lenses. Nor do I use the words "liberated" and "burden" lightly or melodramatically. Unless you have worn really thick spectacles (and I mean spectacles whose lens thickness is measured in inches) you cannot really appreciate what a "glass darkly" they are. For starters, with spectacles, the point of focus is in front of the eye, which means everything appears much smaller or more distant than is actually the case. Also, and especially with thick lenses that require thick frames, peripheral vision is virtually non-existent; wearing spectacles is like wearing a vision straight-jacket, limiting what you can see to a narrow field to your immediate front. Finally, thick spectacles are extremely uncomfortable: in Summer they are hot and heavy; in Winter, they are constantly obscured by rain and fog.

Not that I necessarily felt sorry for myself; I always counted myself more fortunate than the blind or the near-blind for whom no amount of corrective devices proved effective. In so doing, I concede that I was ignorant of the rich lives lead by those over whom I considered myself more fortunate; nor do I deny that my sentiment was occasionally a salve to damaged pride in the wake of the inevitable childhood bullying or adolescent angst. But in general, my feeling was not so much one of self-pity as sheer frustration. I felt trapped in a kind of netherworld, in which I could imperfectly glimpse the possibilities of undiminished vision, but from whose promise I was permanently alienated.

In time, of course, I came to terms with my condition. My vision gradually stabilised (in relative terms), I was able to access the freedom of contact lenses, and I was not prevented in any way from indulging in my love of literature and writing. But I never forgot that particular passage from A Wizard of Earthsea, either; it was at once both consolation and reminder, a kind of bitter-sweet meditation of the Weltschmerz of being.

And so it was that I recently sat in the consulting room of a retinal specialist, considering Le Guin's novel and the reaction of the old man. I had just been informed that I had suffered a detached retina in my left eye, and that it would require surgery to correct. And the sooner the better; indeed, if it was left too late, or not treated at all, the result could be total vision loss in the left eye. How had this happened? As I understood the explanation, it went something like this: as we age, the fluid in our eyes changes, becoming denser and harder. This usually starts in early to mid thirties, and usually has no adverse effects. In my case, however, because my retina was so weak, the change in the eye fluid had caused a tear in the retina, into which fluid had leaked. This fluid had eventually resulted in the retina becoming detached from the eye.

Shortly thereafter, I went under the knife (so to speak) at the Royal Eye and Ear Hospital in Melbourne. The procedure employed was that the fluid would be drained from my eye, a cold laser would be utilised to seal the tear in the retina, and a gas bubble would be dropped in the eye to press the retina back into place. It was a day procedure only, with an overnight stay for observation purposes. I was told it would be done under a local anesthetic, but as it transpired, they put me out completely. Coming out of general anesthetic was quite unpleasant; aside from general grogginess, there was a foul taste in the pit of my stomach. But aside from that, there was no pain; a slight headache, which pain-killers dealt with; a scratching sensation in the left eye which went away after 24 hours; a bruised feeling in the socket, which persisted for a week or so; and a bloodshot eye which gradually diminished. My eye was also puffy and black, like someone had smacked me in the face with a 4x2; but I suppose you can't have surgery and come out of it looking like a fashion model!

And all this just three weeks before my and my Dearly Beloved's wedding! Not that we were stressed (much!). For myself, however, I wasn't so much concerned with the procedure as with what would happen if it were not entirely successful: if there was vision loss, or loss of function in the eye, would that have implications for my hopes to candidating for the ministry? And if so, what else would I do; what calling could I follow, having set myself on the path to that calling which I feel it is my life's purpose to pursue? In the end, I could only shrug my shoulders and allow matters to take their course; there are just some things in life over which we have no control, and about which it is pointless getting upset. Not, I hasten to add, that I was resigned to any sort of fate, nor expecting the worst. Rather, I simply understood that all I could do was place myself in the hands of the surgeons and specialists and let them get on with the job.

Well, it's been two weeks since the procedure, and I am happy to report that, according to my doctors, I am healing nicely. I still can't wear a contact lens in my left eye as the gas bubble still hasn't dissolved fully (I may still be one eyed come wedding time), but at least I can now read and write (unlike the first week and a half, when I could only contemplate the slow passage of time), and I have no troubles getting about (although depth perception is slightly problematic). Also, there should be no problems flying off to NZ for the honeymoon since the gas bubble inserted in my eye should be fully dissolved by then; it looked at one stage as though I would have to have long-acting gas bubbles inserted instead, which would have meant delaying the honeymoon until much later next year.

More importantly, I want to add that I was a public patient. I do not have private health insurance because I cannot, and have never been able to, afford private health insurance, rebates and incentives notwithstanding. Moreover, I have always had a personal view that maintaining a public health system as a primary and not second-rate form of community care is an absolute priority, a matter toward which our tax monies should be focused. The REEH is a public hospital. I was in a public ward. The nurses, despite being obviously hard-pressed by their workload, were attentive and compassionate. The doctors were at once down-to-earth and humorous. I never once felt like a second-rate patient. The REEH was everything a public hospital should be - despite what I am sure were the kinds of shortages in resources and personnel which our user-pays obsessed society has imposed upon the public health system. They were absolutely fantastic, and I have nothing but praise for the entire staff.

It is just a pity that, as a society, we care more about tax-breaks and for the short-termism of immediate gain than we do for the institution of public health willingly funded by the citizenry as a whole.

I am still recovering from the surgery; and although I still don't have access to the full measure of the world's light, thanks to the staff at REEH, I have the same level as I enjoyed before. It is enough.

Talk to you soon,

BB

Quote for the Day: We all know what light is; but it is not easy to tell what it is. (Samuel Johnson)

Tuesday, November 28, 2006

Behaviour, Technology & Population: The Environmental Triad

Both Make Room! Make Room! and Soylent Green have been criticized as overly dependent on Malthusian notions of exponential population growth, and for failing to take account of the remedial effect of increasing technological efficiency. But these criticisms fail to acknowledge the essential truth in both the novel and film: that environmental degradation is largely a product of the First World’s profligacy; and that technology alone cannot solve the ecological dilemma by which humanity is confronted.

These truths are relevant to Australia in two key respects. The Howard Government has declined to endorse the Kyoto protocols on global warming on the grounds that they don’t do enough to limit Third World greenhouse emissions. But the question immediately arises: why should Kyoto place similar limits on the Third World when it is the First World that is largely responsible for the pollution that has destabilized the global environment? Australia is the world’s largest per capita polluter; the United States is the world’s largest net polluter. The onus is surely on both societies to take the lead in reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Secondly, the Federal Government is also making serious noises about building nuclear fission power stations as a "solution" to global warming, as well as indulging in speculation about the possibilities of geo-sequestration. This reflects a worrying obsession with the "quick fix" of technology instead of a preparedness to adopt the hard grind of behavioural change. The approach seems to be: let’s close our eyes and hope someone comes up with a clever invention that gets us out of this mess.

Moreover, population, for all its Malthusian overtones, remains an issue. Much hand-wringing occurs over the alleged failure by First World nations to sustain "replacement level" birth rates; the simple truth, however, is that there are too many people on this planet. Advanced industrial civilizations are mass consumers of resources, regardless of technological efficiency; therefore, mass population only exacerbates the negative effects of mass consumption. In other words, it is simply not possible – never mind sustainable - for the present global population to exist at First World levels of industrial capacity and material prosperity. And nothing we do to make technology more efficient, or our behaviour less wasteful, will change that fact in the longer term.

Thus, a long-term solution to environmental degradation will necessarily involve not just technological initiatives and changes to societal behaviour, but also a commitment to getting the global population levels down. And this is perhaps the most problematic aspect of the environmental dilemma, involving as it invariably must, difficult ethical issues. But the only way meaningful population decrease can be humanely achieved is through managed processes; that is, if we want to avoid the ghastly agencies of war, famine, and disease in the wake of environmental collapse – or the mechanical mass euthanasia depicted in Soylent Green.

The implications of Harrison’s novel and the film it spawned should be clear to most Australians. Aside from noticeable changes to weather patterns that have seen record dry winters and an unprecedented early start to the bushfire season in south-eastern Australia, there has been much media coverage of the Queensland Government’s decision to dam the Mary Valley, and of the dire warnings contained in the recently released Stern report. Australians are aware, as never before, of the consequences of environmental change – and of the long-term inability of technology alone to ward off the worst effects of global warming.

It now appears that at least some political fingers are starting to get twitchy on the panic button. The only question is whether this twitchiness is derived from a realization that we need to do something, or just reflects the politician’s instinct to bend in the immediate breeze of the vox populi.

Talk to you soon,

BB.

Quote for the Day: In skating over thin ice, our safety is in our speed. (Ralph Waldo Emmerson)

Thursday, November 23, 2006

Birds of a Feather

I refer to this specific behaviour as cinema syndrome. Catchy name, isn't it? I define cinema syndrome as the inevitable propensity for people to gather in a space guaranteed to cause other people maximum inconvenience. As a plague, it doesn't kill, main, or injure; but it does annoy, irritate, and frustrate the bejeezers out of you. In fact, I'm willing to bet the irritability caused by cinema syndrome has resulted in more than one person thus afflicted doing something really stupid: such as having a catastrophic row with their spouse, for example, or driving while still in the grip of a rage, thus endangering themselves and others.

What the hell am I talking about? I hear you wonder. Well, let me give you a common example.

Have you ever noticed when you go the flicks that, after the film, people don't file out of the cinema and walk into the wide open spaces of the foyer? Instead, they congregate around the exit, impeding the flow of traffic out of the cinema while they dither about whether or not they need to go to the toilet, or engage in otherwise useless activities such as rubbernecking for friends or family members from whom they have somehow become separated in the interval between leaving their seat and exiting the cinema. Others just stand there talking, right in the middle of the exit, utterly oblivious to the people trying to leave and whose path they are blocking. Worse still, if in trying to get past this obstacle of stationary thoughtlessness, you have the temerity to ask them (however politely) to make way, they give you looks of such lethality the hair on the back of your neck shrivels up and dies.

This is what I mean when I talk about cinema syndrome. It happens at the movies, at the theatre, at rock concerts and orchestral recitals. Any place where you combine large numbers of people with small exits. People can't seem to help themselves: they just stand there making life difficult for the rest of us.

Mind you, cinema syndrome doesn't just happen at the locale for which it is named. It also occurs, for example, on public transport. School kids are notorious for congregating in the doorways and cluttering up the floorspace with their bags, making a virtual obstacle course of any train or tram in which they happen to be travelling. And, yes, I know that often they have little choice because the train/tram is either full anyway, or the size of their schoolbags makes standing anywhere else rather difficult. Frankly, however, I've witnessed too many examples of students (and, it has to be admitted, other passengers) who've quite deliberately positioned themselves right next to the doors because they were too lazy to move to the back of the carriage, or because public safety was less important than the opportunity to gossip afforded by congregating in the entrance. And, for the record, I've also seen enough examples of people nearly breaking their necks as a consequence of being forced to negotiate the labyrinth of bags and students for me to know whereof I speak.

Cinema syndrome also occurs on the footpath. Melbourne's CBD is blessed by having nice wide footpaths; however, some people think this is an excuse to engage in a particularly infuriating form of mobile loitering. And that's not an oxymoron, either; it actually happens. Just ask any person who's been running late for an appointment, or who has otherwise had somewhere they need to get to as a matter of urgency: they'll tell you they'll inevitably encounter a group of people strung out across the whole footpath, strolling along at a genteel pace and idly chatting to one another as though no-one else has anywhere to go. And the most annoying thing is that this oblivion to the needs of others forces you either to go around the offending group by stepping out into the road (and thus into the path of any traffic), or else come across like a pushy bastard by squeezing your way through their strolling skirmish line. And you just know that if you do the former you'll be subjected to bemused looks and thoughts along the lines of "what an idiot"; while, if you adopt the latter course, you risk scorching the back of your head with their glares of outraged propriety.

Not that I'm advocating people should be pushy or aggressive, nor that we should live our lives at the pace of a hundred meter sprinter on acid. However, I really don't think it's too much to ask to suggest that perhaps folks ought to be a tad more aware of their surroundings. Congregate in spaces designed for the purpose: ie, foyers, not doorways! And if you're out and about with a group of friends, by all means walk at your own pace - just don't take up the whole footpath while you do it. That's all I'm asking for: just a teensy, weensy bit of consideration...

Anyhoo, I gotta go. I've just inspired myself to get out there and suggest to my fellow citizens that they stop clogging the s-bend of society.

Talk to you soon,

BB.

Quote for the Day: Moral indignation is 2% moral, 48% indignation, and 50% envy. (Vittoria de Sica)

Monday, November 20, 2006

Three Poems II

It's not the fact that now you walk

with someone else. Nor yet,

that when you kiss, the pain and pleasure

etched upon your face

ripples through the space-time of my love.

It's not the fact that memories of love

grow cold. Nor yet,

that when I think, the image of your face

slowly decays, and carbon-14 dates the time

when you and I -

The prehistory of my heart leaves no trace.

It's only when I wake

and fine her here, cradled in my arms,

I know the thing:

a white dwarf,

dying amid the matter of itself,

outward bound.

Sentinel

What could be more innocent than this?

Love's terrible beauty,

measured in your body's form,

lies next to me.

My arms enclose your waist;

your quick, silent breaths,

patterned to the rhythm of your dreams,

encircle me.

The texture of your tongue and mouth,

the perfume of your hair,

the warmth of eyes now closed

and dwelling on your dreams -

I keep them close, sacred and loved.

Precious one, this is why I lie awake

tonight: to see your aching loveliness,

so vulnerable, yet safe.

Amateur

Dark shapes

hunched against the night:

man and telescope,

we gaze into the sky,

hoping what we find

will resonate with truth.

Do we do this

thinking that we better humankind?

That if

we stare into the dark,

we'll find that point of light

familiar to us all?

Who thinks such thoughts

at times like this?

We see by light

refracted from the red,

the Doppler wail an old cadence:

the siren song of life.

Thursday, November 16, 2006

Like Sand Through the Hourglass....

Not to the forthcoming Victorian state election. As if I could be bothered with the public policy auction between the right-wing Alternative Liberal Party and the even more right wing Liberal In Name Only Party that constitutes an election campaign these days.

On the contrary, I am talking about the pending nuptials between myself and my Dearly Beloved. In one month from today, we shall be Mr and Mrs BB.

To mark the occasion, I thought I'd post this cartoon by Wiley. He's my favourite cartoonist since Larson, and I thought this one pretty well summed it up.

Let the countdown begin!

Talk to you soon,

BB.

Quote for the Day: All tragedies are finish'd by a death. All comedies are ended by a marriage. (Lord Byron)

Tuesday, November 14, 2006

Scenes from the South Island

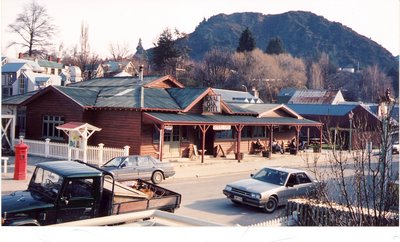

In the New Year, my Dearly Beloved and I will be travelling to the Land of the Long Cloud - New Zealand.

In the New Year, my Dearly Beloved and I will be travelling to the Land of the Long Cloud - New Zealand.Sunday, November 12, 2006

End Times

It has been an emotional time, because I have been associated with the union movement for the better part of two decades. As a rank-and-file member, as a workplace delegate, as an elected honourary official, and as a paid official, I have spent the best part of my working life helping people in the often brutal environment of industrial relations. And I use the word brutal advisedly: I have witnessed some truly horrific and inhumane acts and omissions undertaken in the name of commercial advantage, operational efficiency, or simply as a consequence of the exercise of power.

But I have also seen some moving examples of integrity and compassion. I say this in all honesty: I have met very few HR professionals for whom I have any respect, simply because they were too cowardly, or indifferent, or stupid to conduct themselves with any independence from the corporate line. Most willingly subordinated themselves to being nothing more than the club in the managerial fist, and justified the fact by claiming they were only doing their job. Some, quite frankly, enjoyed the experience of power. But there were a precious few - about half a dozen or so whom I won't name, but if they read this blog will know who they are - who did not separate being a HR practitioner from also having a conscience, or treating people with dignity and respect. And, as time went on, it was these precious few whom I came to admire and respect, because, in many ways, they had a tougher job than I did. And sure, we didn't always agree on issues, and sometimes ended up in the Industrial Relations Commission contesting a dispute; but whether they agreed with me or not was never the issue. I knew these people always acted with principle and professionalism, and more than once they demonstrated their compassion toward people to whom it might have been very easy to be indifferent.

I have also had the immense privilege of working with some of the most talented, committed, and knowledgeable people one could ever hope to encounter in life. It has been inspiring and humbling to witness their commitment to the cause of human dignity, and I have often seen the terrible emotional price they paid for the sake of helping others. Of course, like all humans, trade union officials are not plaster saints: I have seen the incompetent or the indifferent, those who were not cut out for the job and those who simply viewed it as a step to somewhere else. But the overwhelming majority were motivated by an abiding desire to even the balance of bargaining power between the corporation and the individual, and to prevent the strong from victimising the helpless. And most conducted themselves with a courage and persistence and a self-sacrificing generosity that was wonderful to witness.

Ultimately, though, what kept me going were the numerous examples of courage and dignity which I saw displayed by so many ordinary working people under the most horrendous of circumstances. I have seen people bullied and victimised and terrorised who nonetheless refused to yield to fear or the cult of hierarchy; ordinary, everyday, remarkable people for whom their right to dignity was more important than security or popularity or the pressure to conform. And so often it was these same people who, when I thought I hadn't done enough, or achieved a sufficiently good result, told me with disarming honesty just what I had achieved, how much I had changed their lives for the better. The small results were so often the most significant: the mere fact that there had been someone on their side, someone to stand beside them and speak for them was what they most often appreciated. And that was moving and humbling and uplifting beyond my power to describe.

And so it hasn't been easy, making the decision to leave. But there have been other calls on my life growing within me for the last few years; calls which had always been there, but which I had briefly stilled through my work as a union official. But those calls can no longer be stilled. I do not know what the future holds; I have my hopes, but I am aware that I have not been made any promises, either. But, regardless of all that, I know the time has arrived: the roads and strands of consequence have converged, and I need to go forward toward that calling which I feel it is my life's destiny to serve. And so now I have aid aside one vocation, ready to pick up the new.

But perhaps it is not as simple as that. Perhaps the vocation of trade unionism has prepared me for the vocation of ministry; perhaps this is not an ending of one thing, but simply the beginning which toward which that thing was leading. Perhaps it is not a severing of strands but a tying off of loose ends, and their continuance in a new thread. But be that as it may, one thing is over and a new thing has begun; and I am grateful for the old and looking forward to the new.

Talk to you soon,

BB

Quote for the Day: If we do meet again, why, we shall smile! If not, well then, this parting was well made. (William Shakespeare)

Wednesday, November 08, 2006

The Sadness of Pretence

All these scandals have received high publicity for a number of reasons. One involves the predictable public fascination with the salacious; there is a certain voyeuristic element involved. But of especial note has been the satisfaction many have derived from the "downfall" of the men involved: seeing them tumble from their prominent positions, witnessing the "disgrace" of people who had previously asserted themselves as "guardians" of "moral values". I call this the You're no better than the rest of us syndrome. Others call it "tall poppy syndrome", or simply refer to the satisfaction many derive from seeing someone get their "come-uppance". Whatever you call it, there is no doubt that many derive gratification from the "shame" to which these "fallen" figures are exposed.

In one sense, this is understandable. Frequently, these figures have risen to prominence and sustained their influence by peddling to prejudice and fear, by engaging in "crusades" against "moral corruption" and "evils" within society. These activities frequently result in minorities or relatively defenceless sections of society being targeted for no other reason except that they make convenient scapegoats, or useful agencies through which the ambitious and unscrupulous might achieve their purpose. In these instances, people often regard it as "poetic justice" when a figure whom they have regarded as a "bully" or a "bigot" is exposed as having "skeletons in the closet".

Likewise, it is often satisfying to many to see that those whom we regard as having taken the "moral high tone" and indulged in "preaching" are themselves guilty of the very "sins" against which they have formerly railed. We are thus able to dismiss them as hypocrites and award to ourselves the moral "high ground" in the light of the "fallen" person's double standards.

Nor do I exclude myself from this practice. I have often smirked in self-satisfied affirmation upon hearing that this or that conservative politician or religious figure has been "found out". As a "progressive" who has often been vilified by "moral crusaders" (whether individually or as a member of a target group), there is a deep appeal to personal vanity and a sense of one's own righteousness when the other side's "towering figures" are found to have feet of clay.

But upon reflection, I find that this should not be the case - indeed, I should know better. For it seems to me that what these scandals reveal is not the hypocrisy of the people involved, but the sad, artificial pretense that certain theological and socio-political worldviews impose upon humans. Pretences that are a denial of reality - that are a denial of life - and which create impossible expectations which no mere mortal could live up to.

And I know this from my own experience. Many years ago, I knew a young woman who was a member of a conservative pentecostal Christian denomination. Indeed, her father was the pastor of the church she attended. But the more I came to know this young woman, the more I realised how dysfunctional her life was: a spiral of lies, deceit, shame, and despair generated by the fact that her "faith" demanded of her things which she could not possibly deliver and at the same time remain an integrated human being. For example, she was expected to be a virgin until she married; and yet, the "Christian" man she was at the time engaged to (and who was lauded by her parents as a "model" person), was both having elicit sex with her and putting pressure on her to keep the fact secret. Moreover, as time passed, she realised that she was not heterosexual but homosexual: this was her true sexual orientation, and the secret sex she was required to have with her then-fiancee was not only riddling her with guilt, it was damaging her self-identity. Eventually, and due to a variety of reasons, she developed alcohol and drug dependencies, all of which she kept secret from her parents; she could not tell them because she knew that any such admission would be seen as a "failure" on her part, a "shame" and a "disgrace" in which she had "let down" her parents and her church. They would not react with compassion and care and concern - despite the fact that her father was a pastor and her mother a counsellor - but with rage and condemnation.

Nor is this an isolated example. But the point of it is that it seems to me that the kinds of figures who frequently feature in scandals - especially "sex scandals" - are the very people who are worst affected by the artificial milieu created by frantically conservative moralism. In order to be a member of the church, in order to be "respectable" and "acceptable", they have to live a lie. And you cannot go on living a lie: either you will implode psychologically and emotionally, or someone will find out and "expose" you. Especially if you make a career out of pretending to be someone you're not.

Another is the so-called "saving myself for marriage" movement, wherein teenagers are encouraged to vow to "save" their virginity until marriage. I've seen kids as young as thirteen and fourteen wearing wedding bands as a "reminder" of their "vow". Is it just me, or does anyone else realise how unhealthily morbid this is? Aside from the actual obsession with sex and the impression it creates in vulnerable minds that sex is somehow "wicked" or "dirty", has it occurred to anyone how actually counter-productive it is? One survey I saw actually suggested that over 80% of teenagers in California who take such a vow "break" it within 12 months. Why? Because - it seems to me - the obsession with sex, with making it "forbidden", actually increases the potency of its allure; the more you depict something as "out of bounds", the more you make it the locus of otherwise unattainable thrills and excitement. In other words, the more you make it attractive.

And the result? Guilt, lies, deceit, secret double-lives, a cycle of shame and avoidance. Despite their bravado, no teenager likes to know their parents disapprove of them, or are ashamed of them. No teenager relishes the prospect of owning up to their mistakes - especially in the context of knowing they'll get not comfort and support but blame and recrimination. So having succumbed to temptation - a temptation created by the hysteria of the adult community - most teenagers in these circumstances will prefer to avoid the disappointment of their parents and just pretend it didn't happen, or that it won't happen again. Or, if it does, that their parents are "better off" not knowing. All too often, these situations end in tragedy - even if it's the tragedy of a person having to carry an unnecessary load of guilt and resentment with them for the rest of their lives.

I feel sorry for Ted Haggard and others like him. Not because he doesn't think like I do, or agree with my point of view. Just because he has a sad, warped view of "faith" that forces him to live a lie instead of as a complete and fulfilled human being.

Talk to you soon,

BB.

Quote for the Day: The more hidden the poison, the more dangerous it is. (Margaret de Valois)

Saturday, November 04, 2006

The Definition of Loneliness

I've actually been looking forward to this for a long time. Ever since my name went onto the electoral roll, I've waited for my opportunity to undertake jury service. Not, I hasten to add, because I relished the opportunity to sit in judgement on any of my fellow citizens. On the contrary, I have always been aware of the terrible responsibility that frequently rests upon jurors, and my anticipation of jury service was anything but tinged with rose-coloured perception. Rather, I viewed jury service like voting: part of the simultaneous privilege and responsibility of citizenship. Serving in a jury would be both a reminder of my duty as a citizen to strengthen civil institutions through participation, and of my great good fortune of living in a democratic society where the legal process was underpinned by the involvement of the citizenry.

So wouldn't you just know it that when I finally do get summonsed, it couldn't have come at a worst time. Right in the middle of my theology exam. I had actually been anticipating that the exam would be concluded before I was due to report; but it was only after I received the summons that I discovered the exam would be running into the period after my jury service commenced. Accordingly, I was hoping - somewhat reluctantly, I have to admit - that on the day I was summonsed to attend, I wouldn't make it out of the general jury pool. Or, failing that, that I would be able to convince the court that I should be excused.

I and my fellow jurors gathered in the jury pool room. Eventually, the supervisor informed us that of the sixty or so people present, some forty of us would be selected at random to serve as a jury pool, from which a jury would be empanelled for a trial commencing that day. I waited as each name was called, my hope and anxiety in equal portions increasing as I escaped the calling of names...until, right toward the very end, I heard my own name. With a silent sigh, I answered to my name and took my place within the jury pool.

I won't tell you what court was involved, or the nature of the charge. Except to say it was a serious matter. As the jury pool filed into the courtroom, I found to my surprise that I was sitting next to the dock, within touching distance of the accused. I could hardly believe my eyes: the young person in the dock looked all of sixteen. Obviously, they must have been older, but all I saw in that moment was a vulnerable young kid.

Immediately, I was assailed by a wave of compassion. Regardless of who this person was, or what they were alleged to have done, I realised in that moment that here was an individual whose future had not merely been suspended, it had been changed completely, perhaps even eradicated. Obviously, I was conscious of the other side of this particular coin: of the victim of the alleged crime, and that person's family and friends. But as I examined the accused, I could see the emotions flickering across this young person's face: fear, anxiety, helplessness, and a sense of restlessness not unlike that one might expect from a caged animal. Nor was this person acting for the benefit of the jury: as it turned out, most of those who were to be empanelled sat with their back to the accused. I was one of the very few who could see this person's face, see their wide, staring eyes and apprehensive expression.

And the terrible, terrible loneliness. The accused sat in the dock at the back of the court. Their counsel sat at the bar table with the prosecutor at the front of the court, facing the judge. No-one sat with this young person except for a stolid guard who obviously wasn't there for moral support. The accused was utterly, completely, on their own. The fact that they were so young added poignancy to their isolation; they could see the whole court, see their counsel talking to one another, even on one occasion sharing a professional joke with the prosecutor. But this person had no-one to talk to, no-one with whom to share a reassuring smile or even a supportive squeeze of the hand. All they could do was follow the proceedings; and, during moments of intermission when the court's attention was occupied by other matters, contemplate their thoughts.

What was passing through this young person's mind? I wondered. Were they contemplating the possible future that lay before them if they were convicted? Were they wishing that if only they could have their time again, they would do anything other than be in the situation that had ended with them coming before the court? Were they thinking of family or friends? Of ruined prospects? Of the victim of the alleged crime and their family? Or were they simply too numb with fear, with the enormity of their current circumstances to think coherently?

I noted the nervously tapping fingers, the fidgeting feet, the occasionally bowed head. What state of mind did they reflect? What thoughts? What fears? I was overwhelmed; felt sick at heart, felt utterly wretched for this young person, and for the human condition that produces situations like this...

Eventually, my name was called. I explained my situation to the judge, and was excused. And with relief, I might add. I wanted no part of the terrible sadness I sensed was unfolding in this court.

Eventually, the jury pool members who had either been excused or not empanelled were discharged. As we were lead from the court, a burst of sunlight washed across my face. I was suddenly, intensely aware of my liberty, of the fact that I was free to leave that court. And I wondered: would that flood of compassion I had felt for the accused have affected my judgement had I been free to be called and empanelled? I would like to think not, and in retrospect, believe that, like most jurors, I would have judged the case on the evidence. But I would have felt the full weight of my decision, whatever it may have been, having caught in that glimpse of the accused not a possible criminal but a vulnerable human being, terribly, cosmically alone.

As I walked away from the court, I whispered a silent prayer: God be merciful to all those involved - the accused, the victim, and their family and friends.

Talk to you soon,

BB

Quote for the Day: Man's capacity for justice makes democracy possible; but man's inclination to injustice makes democracy necessary. (Reinhold Neibuhr)

Wednesday, November 01, 2006

Three Poems

Launched from dreams to wakefulness,

I lay beneath the covers, listening.

The warmth between my arms was empty air,

the shades within my heart

shadows of your parting kiss.

Launched from wakefulness into my dreams,

I lay beneath the covers, listening:

rain against my window pane.

Kiss

I held you in my arms.

Your heart fluttered,

the captive bird held

within the circle of my love.

I felt the thrill,

the tremble in your bones.

The kiss was light,

yet shook you like a 'quake,

feet of clay. Were you scared,

or just afraid

I'd find the child

hiding in the dark?

In Absentia

I miss -

The eyes, the lips,

whirling,

falling into emptiness,

holding onto life

and joy

and love,

onto thought

and flesh

and time,

when time spent

passes like a winking eye,

like a smile:

fleeting, full,

thoughtful,

like the night,

like the bright

coloured light of dawn,

of the sun rising.

Like the morning sky,

like waking in each others' arms,

dreaming,

laughing, smiling.

I miss -

you!

Sunday, October 29, 2006

Three Down, Twenty-One To Go

But the fact that I've come to the end of first year unscathed (so far!) is a cause for reflection. What has happened to me this year? What do I know that I didn't know previously? What has been confirmed? What has been re-shaped or changed?

I think the process of discovery has, for me, emerged in the form of two broad categories. The first is that I have come to realise how much I don't actually know. Or, more correctly, I have come to understand (or, perhaps, more clearly perceive) the connections that unify the theological web into a single unity. I used to think of theological issues as distinct components, as specialised or discrete bits of knowledge. Now, however, I have come to understand that faith is built on a network of intermeshed contexts, without which, neither the singular nor the whole can be understood. Thus, for example, God cannot be approached outside the context of the Trinity, or apart from Biblical witness, or without reference to the philosophical underpinnings of early Christian theology, or the historical-social setting of the human experience of God, or, indeed, of the broken and inadequate power of human perception. These and many other factors interlink to produce a corporate understanding that underpins, broadens, and deepens the particular.

Personally, this realisation has, for me, been a source of especial excitement. The prospect that there is so much that I don't perceive or understand has not been at all daunting. On the contrary, it has given me a vision of huge vistas and possibilities; there is so much to explore, to learn, to know, a vast richness replete with opportunities for growth and understanding. Coming to realise one's ignorance - or, perhaps more benevolently, one's misguided thinking - is certainly a humbling experience. But this humility is never denigrating; on the contrary, it actually makes one more open, more ready and able to listen and to perceive. It's function is not to destroy confidence; rather, it serves the very purpose of whetting the appetite.

The second category of understanding which I have come to this year is the flip side of the first: not only have I realised how much I don't know, I have also come to understand how much I knew but either didn't know I knew or wasn't able to articulate. So many times during the year, as I've sat in lectures and tutorials listening to my teachers and fellow-students, I've thought to myself: of course! And the sudden light of understanding hasn't been that of revelation, but that of realisation: I had known all along, but hadn't been aware of the fact, or hadn't the means to provide that knowledge with expression. Nor was this simply a matter of appropriate technical language, although that certainly did apply in some cases. Rather, it was more a case of waking up to myself, of presenting to myself that which I already knew, but to which, for various reasons, I had blinded myself.

An example of this concerns sin, and in particular, the doctrine of original sin. This was a doctrine with which I had always had considerable difficulty, not least because I chose to adopt a strictly anthropological perspective and reject the notion of original sin on the basis that Adam and Eve never existed. Therefore, how could "original" humans have sinned, when there were never such persons, much less a Garden of Eden? Or, in the alternative, even if it could be supposed that such persons and such a time existed, how were the sins of my forebears my responsibility? This objection (among others) allowed me to turn away from Christianity for many years (although I never allowed it to turn me away from God and become an atheist); but some part of my mind knew this was semantic trickery, that I was actually being dishonest with myself. And, of course, my studies this year have revealed to me what I always knew to be true: that sin is not mere wrong doing, it is imagining that we can be self-sufficient, that we can exist on our own ground without God; and that original sin refers not to some imagined failure by imagined ancestors to obey God, but to the brokenness of humanity, to the fact that we sin because we are sinful, and not that we are sinful because (or when) we sin. Seen in this light (a light which had always been there, but against which I had turned the shutters of my mind), my objections immediately dissolved, and the knowledge that had for many years lurked in the back of my mind sprang to the forefront of my consciousness.

So, it has been in many ways a constructive and productive year; next year will be very busy, what with being married and the Period of Discernment, and the increased study load, but I hope and have confidence that the same growth, the same surprising discoveries, and the same developing awareness of self and God will continue.

Talk to you soon,

BB

Quote for the Day: ...keep the body within bounds as much as you can...(and) whatever you do, return from body to mind very soon. Exercise it day and night. Only a moderate amount of work is needed for it to thrive and develop. It is a form of exercise to which cold and heat and even old age are no obstacle. Cultivate an asset which the passing of time itself improves. (Seneca)

Wednesday, October 25, 2006

History Repeated

The Peloponnesian War was a series of disastrous conflicts between the rival city states of Sparta and Athens between 472 and 404BC. They had emerged from the Persian Wars of the previous century as the premier city-states of the Greek civilisation: Athens built up a maritime league which, over time, became a subject empire; Sparta became the dominant land power, famed for its military might and the militant rigidity of its society. Without going into details, the Peloponnesian War eventually drew in all the city states of Greece, exhausting both Sparta and Athens, and leaving the way open for the subsequent subjugation of Greece by Phillip of Macedon, and his son Alexander the Great.

I recently read a section of the book discussing the disastrous Athenian campaign in Sicily, which ended in the annihilation of the entire expedition, and came across the following remarkable passage:

Most historians agree with Thucydides in blaming the continuation of the Sicilian campaign on the greed, ignorance and foolishness of the direct Athenian democracy. But the behaviour of the Athenians on this occasion is the opposite of the flighty indecision that is usually imputed to their democracy. They showed constancy and determination to carry through what they had begun, in spite of the setbacks and disappointments. Their error, in fact, is one common to powerful states, regardless of their constitutions, when they are unexpectedly thwarted by an opponent they anticipated would be weak and easily defeated. Such states are likely to view retreat as a blow to their prestige, and while unwelcome in itself, it is also an option that puts into question their strength and determination and with it their security. Support for ventures such as the Sicilian campaign generally remains strong until the prospect of victory disappears. (p. 296)

Do I really need to spell out the parallels which this conclusion has with respect to the present damnable tragedy in Iraq? Who, upon reading this passage, could not help but conclude that the situation facing the Athenian republic in Sicily is the same which now faces the so-called "Coalition of the Willing"? Let's tease out the strands from Kagan's conclusions, and see what they hold for us today.

1. The expectation of victory. Clearly, those who planned the invasion of Iraq expected a clear and decisive victory after only a relatively short period of combat. In part, this expectation was based on the experience from the First Gulf War, in which US-led forces routed the Iraqi occupation of Kuwait. Mostly, however, it seems clear that the leaders of the "Coalition" simply didn't expect the level of domestic opposition that has materialised in the years since "military operations" ended. Indeed, they expected to be welcomed as liberators, as saviours from the tyranny of the Hussein regime. And, in the beginning, it seemed as though these expectations were justified. The Iraqi forces were routed a second time, and the remnant militia resistance crushed after a further, although acceptable, period of fighting. Since that time, unfortunately, Iraq has become a cause celebre for jihadists - just as Afghanistan did during the Soviet occupation of that country. Moreover, militant Sunnis, who were in power during the Hussein regime, have coalesced into an effective resistance against the occupying forces, and the majority Shia and minority Kurdish populations. The expectations of victory have thus dissolved as the conflict in Iraq has morphed into a multi-faceted war - both an armed struggle for liberation and a civil war between competing ethnic and denominational groups - which the planners of the Iraqi invasions clearly didn't foresee.

2. The blow to prestige. As the situation in Iraq has steadily deteriorated, the leaders of the US, UK, and Australia have repeatedly urged that we "stay the course", that we not "cut and run", and thereby "hand victory" to the "terrorists". In recent times, these statements have taken the form of arguing that any withdrawal from Iraq before "the job is finished" would hand the jihadists a massive propaganda victory upon which they could recruit further adherents and thereby threaten the West directly. What are these arguments other than an appeal that we not, through withdrawal, allow a jihadist-inspired blow to our prestige? Leaving aside the fact that the Iraqi situation will now probably result in some humiliating withdrawal sooner or later - just as was the case in Somalia - it seems clear that the leaders of the "Coalition" realised some time ago what a foreign policy quagmire Iraq had become; thus, appeals to "stay the course" were really just attempts to mitigate their responsibility for the whole fiasco behind an appeal to populist patriotism. Moreover, it seems self-evident, even before any withdrawal has occurred, that the situation in Iraq has placed the West at greater risk of terrorist attack: as the bombings in Madrid, London, and Bali have so appallingly demonstrated. Thus, the appeal to national security is a furphy; that security has already been compromised by the invasion of Iraq itself. But the appeal to prestige is a powerful one, because it is essentially an appeal to national egotism; and it is through pandering to this egotism that popular support for the invasion has been sustained for so long.

3. Popular support. At the time of the invasion of Iraq, public opinion - at least, Australian public opinion - was decidedly against the intervention. However, this quickly swung around in the aftermath of the speedy "Coalition" victory over the conventional forces of the Hussein regime, and the subsequent nullification of the pro-Hussein militia. Moreover, there was a preparedness on the part of many citizens to believe - or, at least, to accept as a valid causus belli - the justifications for the war based on the alleged possession of weapons of mass destruction by the Hussein regime, and of its supposed links to the al-Qaeda terrorist organisation. These factors combined to keep public support for the war in Iraq at high levels for a substantial period of time - long enough, indeed, to ensure the re-election of the Bush, Blair, and Howard governments in the US, UK, and Australia respectively. Now, however, that support has evaporated. In part, this is due to the fact that many people feel they have been lied to by their governments, especially in light of the fact that it has now been demonstrated that the Iraqis did not possess WMDs, nor were there any links between the Hussein regime and al-Qaeda. The reality, however, is that there was a substantial and vocal minority in the countries of the "Coalition" who were articulating these truths at the time of the invasion. In other words, public support for the Iraqi invasion has disappeared largely because the citizenry now recognise the conflict for the lost cause that it is, and feel both the embarrassment to national pride this occasions, as well as a sense of shared culpability for the disaster. Public opinion has shifted because a swift victory has not eventuated, a victory that might otherwise have enabled the public to salve its guilty conscience.

The upshot of all this is that the "Coalition of the Willing" now finds itself in precisely the same situation as the Athenian city-state: having over-extended its resources, it now faces a catastrophic military defeat, as well as the socio-political-economic consequences arising from that defeat. Indeed, it is not clear that the "Coalition" will be able to maintain itself in those spheres where its activities are universally acknowledged to be legitimate - such as Afghanistan, for example. And that will undoubtedly produce the kind of propaganda coup the jihadists are longing for: a coup they will be able to exploit for recruitment purposes. Thus, the security of the West has already been undermined on two fronts: by the short-sightedness and dishonesty of those who planned the invasion of Iraq; and by their stubbornness that has made a bad situation worse.

And the accessories in this whole melancholy affair are the public, who, for the sake of expediency over conscience, allowed themselves to be persuaded to both the justice of the invasion and the merits of the occupation.

Talk to you soon,

BB

Quote for the Day: History is the sum total of the things that could have been avoided. (Konrad Adenauer)

Sunday, October 22, 2006

C S Lewis: Christian Stoic

This approach to Lewis is a nonsense, not least because it does a grave injustice to the man himself and the complexity of both his faith and life experience. Lewis was not an ecstatic Christian, much less an "evangelical" in the sense conveyed by those presently making the aforementioned triumphalist noises. Like most people, Lewis' Christian faith was a process, an ongoing and ever-developing evolution based on his experience of being, and the conclusions to which his reflections on that experience lead him. Nor did it become "fixed" after his conversion: the death of his wife, Joy Davidman, forced him to confront the meaning of his faith in the context of mortality, thereby stripping away the many comfortable assumptions and complacencies with which he had hitherto associated Christian belief and practice. It was an experience that rocked him, and redefined his understanding of faith.

This is a side to Lewis which those presently singing Lewis' praises conveniently ignore. And it is a side that is fully explored in the film Shadowlands, based on Lewis' relationship with Joy Davidman, and in Lewis' own book, The Problem of Pain. These reveal that, far from being the "ecstatic" Christian infected with a simplistic approach to faith and being, Lewis was in fact a powerful thinker and feeler of faith who explored the depths of his being and life experience in order to ensure the integrity of his relationship with God. This was frequently a painful process, and perhaps sums up why he once described himself as the most reluctant atheist, and the most incredulous Christian, in England.

Both Shadowlands and The Problem of Pain explore a very simple, yet exquisitely profound, question: if God were good, why do humans suffer? Shouldn't the goodness of God ensure that God's creation is free from pain and misfortune? Isn't saying that God is good just wishful thinking? Indeed, doesn't the existence of pain and suffering and evil point to the fact that God is not good - indeed, that God doesn't exist at all?

Shadowlands responds to this question by suggesting that, in placing human happiness at the centre of creation, human beings are in fact making a grave mistake. The point being that it's not actually a question of whether God wants us to be happy; God doesn't want us to be unhappy, either, it's just that our happiness is not the issue. What God wants is for people to grow up, to leave the nursery of existence so that we can respond to God as fully rounded creatures; so that we can be who God desires us to be, instead of one-dimensional beings lacking the substance of creation. In this context, suffering is the vehicle through which God calls us to wake up to ourselves. Humans are like blocks of stone being shaped by a sculptor's chisel; the blows of the chisel cause us inestimable pain, but they are also what make us whole and complete. In other words, suffering is not a thief, robbing us of equanimity and innocence; rather, it is the agency through which we are stripped of our life-denying delusions.

The Problem of Pain tackles the issue from a slightly different perspective. It doesn't attempt to describe the nature of suffering; rather, the book seeks to elucidate why suffering occurs. Lewis argues that humans suffer because they exist in a condition - the created universe - that is other than God. Lewis affirms that the universe is God's creation, and the creation is good since it represents an articulation of God's loving will. However, being other than God, creation cannot share in the perfection that is God; creation can only aspire to communion with God, and since this aspiration naturally arises from a self-awareness of imperfection, suffering is implicit in existence.

However, Lewis proposes three consolations that mitigate against what might be a rather gloomy conclusion about the nature of being: